- Home

- Paterniti, Michael

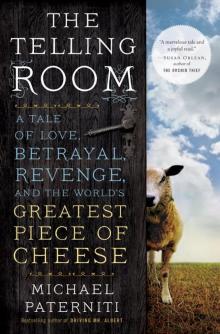

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World's Greatest Piece of Cheese Page 2

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World's Greatest Piece of Cheese Read online

Page 2

“It’s rich, dense, intense,” sang Ari, “a bit like Manchego, but with its own distinct set of flavors and character.”

There was something about all of it, not just the perfection of Ari’s prose, but the story he told—the village cheesemaker, the ancient family recipe, the old-fashioned process by which the cheese was born, the idiosyncratic tin in which it was packaged—that I couldn’t stop thinking about, even as I went on to contend with misplaced modifiers in a passage about marzipan. It occurred to me that there we were, living through cursed 1991, in a crushing recession—when the national dialogue centered around whether Clarence Thomas had uttered the question “Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?”—and along came this outrageous, overpriced, presumptuous little cheese, almost angelic in its naïveté, fabulist in character, seemingly made by an incorruptible artiste who, with an apparent straight face, had stated that its high price tag came because it was “made with love.”

Was this for real?

I went to the deli. At $22‖ a pound for the cheese, I had no intention of buying any. I’d come, however odd it sounds, to gaze upon it. Thus I timed my visit for in-between rushes. I picked up the finished newsletter at the door and stood for a while, reading as if the words were not only brand-new to me but the most fascinating thing I’d ever had occasion to trip over. I watched a few other nicely dressed people—quilted jackets, colorful scarves—reading it, taking pleasure in their pleasure. Then I dove in, jostling through holes in the line, moving across the black-and-white-checked floor until I found myself face-to-face with the cheeses behind the nursery glass: There were the Manchego and Cabrales, Mahón and Garrotxa … and there was my cheese. It seemed to hover there, apart in its own mystical world. It came in its white tin with black etching that read PÁRAMO DE GUZMÁN. The package, which was almost oval in shape, bore the emblem of a gold medal for supreme excellence above all other cheeses, an honor from some agricultural fair, it appeared. And perched there in the display, before a pyramid of the tins, was a piece cut into three wedges. Unlike its paler Manchego and Mahón brethren, it possessed an overall caramel hue. It may sound strange to call a cheese soulful, but that’s what this cheese seemed to be, just by sight. It had traveled so far to be here, and from so long ago. I let myself fantasize about what it might taste like, as I could only fantasize about a gourmandizing, dandy’s life in which I might pen the words “… discovered it by chance in London.”

And this is when an odd shift occurred inside: That little handmade cheese in the tin, and its brash lack of cynicism in a rotten year, gave me a strange kind of hope. I sensed the presence of purity and transcendence. I felt I knew this cheese somehow, or would. It sat silently, hoarding its secrets. How long would it wait to speak?

A long time, as it turned out. But when it did, the cheese had a lot to say. Unlike that day in 1991, when I felt so pressed to leave the deli in order to put the finishing touches on another one of my overheated homing pigeons of prose, it became nearly impossible for me to walk away.

* Mike Tyson, Jeffrey Dahmer, Pee-wee Herman.

† Mine was entitled Augie Twinkle’s Lament, and detailed—some might say excruciatingly—the progress of a minor league pitcher to his final game on the mound, where, after being shelled, he exits over the center-field fence, discarding his uniform, piece by piece, in grief-stricken striptease. From there, left only in his codpiece, he goes on a laundry-stealing binge … and the rest, you’ll have to trust me, is heartrending, humorous, and deeply compelling.

‡ In a New York Times article from the Business section on May 3, 2007, about the populist rise of Zingerman’s, Michael Ruhlman, a food industry expert and writer, summed up the deli’s success over the decades like this: “There’s not a lot the consumer can do, really, to get Iberian ham, but Ari can.”

§ We ended up at Dalí’s seaside villa in Cadaqués, where a friend and I crept to the door at midnight to hear the artist’s favorite music, Tristan and Isolde, at full volume. When our knocking went unheeded, we retreated to Dalí’s high garden wall and drank two bottles of wine, which, along with high winds and a bevy of bats, fanned the flames of that haunted night until, terrified, we leaped at some sound and, entirely misjudging the drop, ended up sprained and bloody, limping miles before we found our backpacker hostel again.

‖ Twenty-two dollars equaling eight chili dogs, or seven falafels, or five bibimbaps, i.e., a week’s worth of dinners.

2

THE OFFERING

“Ambrosio Molinos, it’s your time to kick ass!”

ONCE UPON A TIME, IN THE VAST, EMPTY HIGHLANDS OF THE Central Plateau of Spain … in the kingdom of Castile … in a village on a hill … on a bed in a house where the summer temperature hovered at one hundred degrees … a woman named Purificación lay writhing in labor. For hours the baby’s soon-to-be father had come and gone from the dark bedroom as the woman, sylphed in shadows, rode the wave of each contraction. “Anyone here yet?” said the man, smiling, sipping a cold drink. His wife, a woman of owlish beauty and a certain refinement, said to the midwife, “Get that donkey’s ass away from me!”

Eventually, the baby was born—in the same room, on the same bed, beneath the same roof as his great-grandfather—making him the youngest of three boys belonging to the husband and wife. He had almond-shaped eyes, a body as hefty as a bag of oats, and, even then, lungs that never quit, emitting a loud, gravelly cry. He was not to be overlooked. He ate more than his brothers; slept less. And he had inordinate passion. From the beginning, he endeared himself to his parents by loving them as hard as he could, with an exquisite kind of ardor. When he learned to walk, he followed them everywhere; when he could speak, he spoke to them.

Incessantly.

While basking in his mother’s love, he came to idolize his father. But it wasn’t just that: From the start, he wanted to be his father, an immensely likeable, tough-minded farmer—of big ears and strong, curled fingers the reddish color of the earth here—who had a story for any occasion, a punch line for every dull moment. Each morning, his father zipped himself into his mulo, his blue farmer’s jumpsuit, put on his black beret, and, whistling contentedly, strode the eighth of a mile to the barn along a dirt path that looked down on the high flatlands of Castile, those harsh, empty steppes that make up Spain’s Meseta and that bring scouring gales and then burning sun. Living half a mile above sea level, the Castilians often described their weather as nine months of winter and three months of hell.

This was 1950s Spain, bitter times to be a farmer, bitter times to be a Spaniard. In the second decade of Franco’s dictatorship, poverty was a fact of life; there was little food or electricity in the hinterlands.* Meanwhile, people were migrating in droves away from the semiarid Meseta to the big industrial cities—Bilbao, Barcelona, Valencia—while those left behind farmed the land mostly as they had for centuries, plowing, planting, and threshing by hand. Even the language of the fields was antiquated. Sometimes the boy’s father would greet a friend by proffering a hand with an old salutation that translated as “Hey, shake the shovel.”

The village in which they lived bore the name of the Guzmán family, prominent nobles (statesmen, generals, viceroys) instrumental in the workings of the kingdom of León beginning in the twelfth century. Sometime along the way, a Leonese monarch had bequeathed the Guzmáns 3,000 hectares in the Duero River region for a retreat. In the 1700s, Cristóbal Guzmán built the castle—known in the village as the palacio—over the span of sixty years, as an exact replica (if seventeen times smaller) of the family’s castle in León. Around it, the village flourished, populated at its height by thousands of inhabitants whose patronage sustained restaurants and bars, barbershops and several markets. Though the father—and his father, and his father’s father, and so on—had lived his entire life in the village, it was unclear how deep the family roots ran in the region, even as they flourished. At the height of the family’s influence, they’d come to own the palace. But by the 1950s, the family was in

the process of diminishment, losing more of their field hands to the city as they sold off more of their land. The father had an uncanny knack for making the worst of times seem like the best of times. No matter what the crisis, he remained undaunted in his happiness, singing and drinking his homemade wine. He played cards at crowded tables and told story after story, some about his youthful indiscretions, meeting girls in the fields for the old chaca chaca, some about his days in Morocco with the Spanish army, where the troops seemed to spend more time changing punctured truck tires than anything else. One he loved to tell had occurred when he was younger, when Castile was being heavily bombed by planes during the Civil War. Whenever the church bells tolled a warning, everyone ran and hid in the caves that pocked the countryside here. Except for him and his friends. They would jump on their motorbikes and, beneath the roar of fighter planes, leaning low over the handlebars, they would gun the twenty miles to the nearby city of Aranda de Duero, where they found all the restaurants and bars abandoned, with food and drink still on the tables. The perfect comida: a partial chuleta and freshly poured red wine, a piece of fish and cerveza, a half-eaten flan with digestif. All the better if there was some cheese on the table, for he adored cheese. They went from establishment to establishment until the bombing ceased, and with the first signs of a return to normalcy fled again, zigzagging back up the hill to home.

And so it was after this man—the happy-whistling guzzler of life, the father-farmer-gadfly—that his baby was named: Ambrosio, suggesting the food of the gods, but meaning “immortal.” After a time, the villagers called father and son “los dos Ambrosios,” the two Ambrosios, which later was shortened to “los Ambrosios,” such was the power of their stamp on each other and the town. If you were talking to one of the Ambrosios, it was understood that you were talking to both of the Ambrosios, and all the ancestral Ambrosios, too, even poor great-grandfather, whose ashes were kept in a porcelain vessel in the downstairs dining room, partly in memoriam and partly to make them laugh, as they did, at the misspelled inscription on the jar: Anbrosio.

FOR A CERTAIN KIND of boy, the kind that the younger Ambrosio happened to be—a bit rough, mischievous, full of irrepressible joy and physical energy—Guzmán was a wonderland of ruins and hiding places, broad fields and indentations called barcos, perfect for ambush. The main street wound upward, snaking between the stone homes, past the church to the palace, past caseta and pig barn, out into a whole other infinite world above—what was called arriba here, a polar cap of fertile soil. In this landscape, Ambrosio ran feral with the local kids, playing la talusa and linka. Even in school, he dreamed of his afternoon freedom, when he’d be at play again, or hanging out at one of the natural springs or fountains (where the people did their wash, collected their water, filled tanks for irrigation). He celebrated the village’s annual fiesta by keeping himself awake for as long as he could over the course of five September days: to be chased by the exploding bull—a man dressed in a costume with Roman candles for horns—and watch the fireworks and sing jotas and dance with the grown-ups. He bore witness to the wonders of the outside world, on those occasions when they penetrated. Sometime in the sixties, Gypsies brought the first moving pictures to town, projecting them on the side of the palacio, old black-and-white films from the thirties. Another time, a magician named Barbache the Seal-man balanced an enormous hand plow on his nose. If he’d sneezed, he would have chopped himself in half.

Above all, there was the bodega.

This region of Castile is littered with bodegas, handmade caves dating back to a time before refrigeration. In Aranda de Duero, the Bodega de las Ánimas, built in the fifteenth century, is a maze of three hundred caves, equaling seven miles of underground tunnel, in which seven million bottles of wine are produced each year. In Guzmán, there existed two dozen or so caves, located in the hill that marked the village’s northern boundary. Some of the bodegas here were said to date back as far as the Roman occupation of Spain, just before the birth of Christ. Each autumn, the fruits of the harvest were brought to the caves and stored—bushels of grain, vegetables, and, in particular, cheese and wine, the latter transported in casks made from cured goat carcasses—to be accessed during the long winter and spring. Legend had it that a man would sit in a room built above the cave and itemize what went down into the cellars. This room became known as el contador, or the counting room.

As all the families in the village built or inherited bodegas, they also added these counting rooms, sometimes sculpting a foyer and perhaps stairs that led up to a cramped, cozy space that included a fireplace. Soon, people gathered at the contador to share meals around a table and pass the time. And as the centuries unfolded, as refrigeration techniques improved and the caves came to serve a purpose less utilitarian than social, the room took on the other definition of contar, “to tell.” The contador, then, became a “telling room,” or a room in which stories were told. It was the place where, on cold winter nights or endless summer days, villagers traded their histories and secrets and dreams. If one had an important revelation, or needed the intimate company of friends, one might head to the telling room, and over wine and chorizo, unfolding in the wonderfully digressive way of Castilian conversation, the story would out. On weekends, casual gatherings might last an entire day and night, with stories wandering from details of the recent harvest to the dramas of village life to perhaps, finally, the war stories of the past, all accompanied by copious wine. In this way, the bodega, with its telling room, became a mystical state of mind as much as a physical place. It was here where the young Ambrosio first fell under the trance of his father telling stories.

Something about those stories chimed loudly inside the mind of the boy, something he could never have articulated at first, but that insisted itself over time. It was a feeling of wonder, an aliveness that came in the timeless hush and clamor of the telling room, in the presence of his father narrating stories. Young Ambrosio was transfixed. He would listen for hours, and then think about the tales afterward, haunted by some weave of detail his father had spun. As garrulous as the boy was, he had the same Pavlovian response to any story being told: He would shut up and listen in a state of mesmerized joy.

Ambrosio possessed no interest in school, and yet his mother had dreams that maybe one day he’d become a doctor. Like his brothers, he was sent to Catholic boarding school at a young age, about fifty miles away in the Castilian capital of Burgos. His real education, though, came in the streets and fields of home, watching the ways of the farmers, collecting the stories that filled the airspace of life here. He spent more and more time out beyond the clustered houses of the village, in that unbroken landscape stretching for miles, a patchwork of vineyards and wheat fields, walking with his father or the old men. The Meseta was littered with stories, too, there like stones to pick up. What occurred in the vineyard known as Matajudío—or Jew Killer Vineyard? What was the strange collection of perfectly round rocks, like pterodactyl eggs, doing embedded in the earth in the Barco de Palomas? Or the broken stars of bone fragments in the High Field?

So he listened, and as he traveled his patch of the earth, he asked himself over and over, What happened here? Even as a child, Ambrosio took the lead of his forebears: He spoke to ghosts.

EVENTUALLY, AMBROSIO ENTERED A new kind of restlessness, wandering in search of stories and storytellers, peers with whom he could align himself for life. He started down the hill, in the neighboring village of Quintanamanvirgo, where people seemed more inward and shifty. The village was known by those in Guzmán as el pueblo de los toros, because it was said the inhabitants hid in the dark of their alcoves like cowardly bulls when released into the bright center of a bullring. But those people had a story, too, about a secret tunnel that ran through the mesa, joining them to the spirit world.

Another village, Roa, lay beyond—larger and more raucous, self-assured if not prideful, with a multitude of stores and bars and, most important, a flock of young people like himself. It was here that A

mbrosio first heard a story, “The Asses of Roa,” which he himself later perfected.†

And finally, the outer ring of Ambrosio’s universe became the metropolis of Aranda de Duero, his father’s wartime watering hole, where his best friend, Julián, lived. They’d met at nine years of age, playing basketball for their separate boarding schools. On the court that day Ambrosio was assigned to cover Julián, who was tall and thin, with brown hair. The kid had gangly legs, long arms, and spindly fingers, hands exactly like Ambrosio’s—and a body exactly like his, for that matter. They both had big knees. If their baloncesto careers were short-lived, something more lasting took root that day. In the changing room, Ambrosio heard a familiar singsong accent, and being congenitally extroverted, he sought out the opposing team and said, “Which one of you is from Aranda?”

Shy and introverted, Julián blushed and raised his hand. “I am,” he said. “Why?”

“Because I’m from Guzmán,” said Ambrosio.

It turned out that Ambrosio’s cousin Nacho was Julián’s best friend. Julián named others in his group of friends, and Ambrosio said, “Those are friends of mine, too.”

“If you’re Nacho’s cousin, then why don’t I know you?” asked Julián, and a memory clicked for Ambrosio. A family gathering, a Communion party a few years earlier, when they were all of six. “You were smoking cigarettes in the stairwell, and I smoked with you,” Ambrosio said. And that had been it.

A beautiful beginning.

If Julián was outwardly more serious, Ambrosio appreciated his stealthy bemusement at life, his sidelong smile and sly humor. And Julián loved Ambrosio’s shock-at-all-cost abandon, the impulse that led him, time after time, to be expelled from the Catholic schools he attended. Ambrosio was the ringleader and carnival-maker; Julián became his happy conspirator.

They walked the streets yelling silly things at passersby. They hunted in the fields, not great shots like Ambrosio’s brother Angel, but good enough to kill the occasional rabbit. One day they felled a wild boar and shared it with friends at the bodega, as Ambrosio played his guitar and sang. They took any excuse to be together. At dances and parties—for soon their focus was on women and wine—they might catch each other’s eye over the heads of others and communicate telepathically: a pursed smile, a cocked eyebrow, a wink said it all.

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World's Greatest Piece of Cheese

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World's Greatest Piece of Cheese